- Home

- James Grayson

The Shadow Artist Page 2

The Shadow Artist Read online

Page 2

Now, though, Josef was no different than a racehorse with a limp.

Lockard exhaled, watching the vapors of his breath disappear. Then he set off.

It turned out he was wrong, which pissed him off, but it took only fifteen minutes to reach the house, and he negotiated the garage’s side door in less than three seconds.

It was unlocked.

Mistake number two, Mr. Faris.

He placed his hand on the hood of the car in the garage. Cold. Josef had been home for a while. Lockard couldn’t make out the model of the car, but it looked to be some sort of Fiat or maybe Opel. Garbage, either way, and useless in the mountains, especially in this weather. Still, Josef hadn’t been extravagant.

Yet.

Lockard took a knee to untie and slip off his boots. Holding them in one hand, he stepped to the interior door, placed them aside, and waited.

Faint sounds of an active household echoed from inside. Josef’s two children were both home, and so was his wife. No sound from Josef, but Lockard was not concerned by that. The man was there, no question. He would honor the banker’s requested time for this call.

Lockard reached up, swiveled the knob a hair, and then a bit more, feeling the latch yawn before pushing it open an inch. He paused again and listened. Same sounds, about twelve to fourteen feet away, and with no rugs in the hallway, they created a small echo. It sounded as if the whole family was in the living area at the other end of the house.

Lockard pushed the door fully open, swept inside, and eased it closed again, careful not to let the latch click. Taking in the smell of roasted pork—probably odojak, traditional whole piglet—he moved sideways down the hall and slipped into Josef’s home office.

The lights were off, but that was fine. He had studied the layout on his last visit.

Lockard strode over to the desk and tested the chair. Well oiled, so he took a seat. Then, regulating his breathing to temper any excess adrenaline, he waited.

Eleven minutes later, Josef called to his wife as he walked down the hallway toward the office. He spoke in the South Slavic dialect used these days by most Bosniaks, the traditional Muslims who’d survived the ethnic cleansing war of the nineties to remain in Bosnia. Lockard did not speak the language fluently, but he understood enough from other Slavic training to know Josef had told his wife he needed some privacy and to keep the children from disturbing him.

By the time Josef closed the door and turned around, Lockard had his HK45 Tactical pistol trained on Josef’s head. Though long retired from the SEALs, Lockard still favored the Heckler & Koch for its reliability, accuracy, and the extended threaded barrel, on which he’d fastened an Osprey sound suppressor for the occasion. Wearing the snow-whites, he must have looked like an apparition to the poor man.

Josef opened his mouth to yell.

Lockard shook his head an inch, side to side.

Josef closed his mouth, glanced at the door, then back at Lockard. “How did you—”

“Josef. We have been friends for many years, haven’t we?”

“Yes.”

“And how is your leg today, in this cold?” Lockard glanced down at his own winter gear.

Josef took a step toward the door. “It aches.”

“Yes, old wounds do that,” Lockard said. “Come closer please, Josef.”

Josef eased forward, eyes wide.

“Where is the rest of it?” Lockard placed the HK on the desk.

“I don’t—”

Before Josef could finish the sentence, Lockard had sprung from the chair, secured him in a headlock—not easy, as Josef was much taller than he—and stuffed one of his thick, synthetic-down gloves in the man’s mouth. Josef grunted and Lockard pulled him to the chair. He drew four thick plastic zip ties from his pocket and secured each of Josef’s limbs to the seat. He was careful to keep the straps over clothing, to avoid evidential rubs or bruises.

Immobilized and muted, Josef struggled for a moment, and then his eyes filled with tears.

“Josef?” His wife called from behind the door. “Are you all right?”

Lockard bent down and whispered close to Josef’s ear. “Don’t make me kill the children. Tell her you will be out in five minutes.” He waved the HK and Josef nodded.

Lockard pulled the glove from Josef’s mouth. He coughed, and said, “A few more minutes, then I’ll be out.”

She walked away without answering.

Lockard said, “Where is it?”

Josef glanced at the closet.

Lockard walked across the office and opened the double doors. A tall metal file cabinet sat flush against the wall. “Here?”

Josef looked away. “Behind the files. There is a loose board.”

Lockard tugged back the cabinet—good thing it was empty—and peered behind it. He thumbed a long board, causing it to swivel open.

Well hidden, Josef. You should have kept it that way.

He reached in, found the handle, and pulled it out from the wall space. Josef had kept it in the same aluminum Zero Halliburton case Lockard had given him over a week ago. Placing the case on the desk before Josef, Lockard said, “I assume you changed it. Let me guess, your birth date, or maybe your wife’s?”

“My son’s,” Josef said. “July, the fifth.”

Typical. Lockard reversed the numbers – almost all Europeans, Eastern and Western, listed the day first and then month – and pressed the two latches open to find ninety-nine thick stacks of US dollar bills. Just under a million dollars.

Key word—under.

“You took a trip to London.” He tilted his head at Josef. “And Monte Carlo.”

“It was for my brother. He is sick.” Josef paused, and looked down as he said, “And he likes the casinos.”

“Where is the rest?”

Josef nodded to the desk.

Lockard pulled open the drawer and searched, careful not to thump Josef’s fingers. The near-empty stack of hundreds sat under a sleeve of papers. He dropped the anemic pile into the briefcase, snapped it closed, then pulled out a small, clear vial of resin and held it up. “This will make you sleep. So I can leave without problems.”

“I won’t say anything, I promise it. Please.”

Lockard uncapped the vial.

“You needed me,” Josef pleaded.

“You were a great help. I appreciate that.” Lockard grabbed Josef’s hair and pulled his head back. Stuffing the vial between the man’s lips, he shook the milky liquid into his mouth.

Lockard held Josef’s mouth and nose shut as he waited for the swallow, and kept them covered until the convulsions began. Josef spasmed against the restraints, eyes bulging wide as the chemicals reached his bloodstream and his breathing became labored. Thirty seconds later, his bowels released and his body slumped in the chair.

The massively condensed dose of Gonyaulax tamarensis, a neurotoxin derived from mollusks, caused almost instant paralysis and lung failure. Any autopsy performed would show a simple shellfish poisoning. Josef hadn’t suffered.

Lockard cut off the zip ties and arranged the body into a more natural position, leaving the eyes open. Lifting the case, he then walked to the door, turned, looked around the room, and listened. The three remaining people in the house were farther down the hall, one playing a mistuned piano as the other two laughed.

Satisfied, Lockard slipped outside and back into the white night.

Three

Evading the police was easy. Focused on the destruction of the restaurant, not one officer glanced at Alex as she’d snuck past, slipped a set of keys from the valet stand, and relieved the restaurant lot of a black Mercedes. Sadly, the owner wasn’t going to need it anymore.

Alex steadied her arms on the steering wheel as she sat parked across the river from the restaurant, shielded by two large stone buildings adjacent to Victoria Embankment. Smoke twisted skyward in a giant black funnel, scarring London’s picturesque skyline.

Did my father do that?

He was de

ad this morning. He was dead this afternoon. This evening, up until ten o’clock, Edgar Winter was still dead. Now he was alive, and dozens of innocent people were not. Alex gripped the wheel so hard her hands began to shake.

Eighteen fucking years.

Taking deep breaths, she loosened her grip long enough to pull the mobile from her satchel and switch it on. After waiting a full minute to sync to the data network and update, she checked for text messages, e-mails, phone calls. Nothing. As far as Operations was concerned, Alex was in a blackout. Deputy Director Moss would know she hadn’t completed the assignment when she didn’t report in from the airport later today.

Exhaling hard, Alex dug back into the satchel, trading the phone for her sketchbook, and clicked on the overhead light. She flipped the pages until she found the scene she’d drawn no fewer than a hundred times. From all different aspects, the illustrations ranged from simple line sketches to full-fledged, detailed drawings.

Alex chose a sketch that was midrange in perspective. It undulated with the snaking bend of a shallow chalk stream, its smooth white sides and bottom in milky pastels as it meandered through the countryside somewhere in the western UK. The summer sky glowed upon grass that was overgrown at the banks. The houses seemed smaller than they would in the stark graying months of winter and the large red brick mill lay unseen behind her vantage point, but the full meadow stretched all the way to the horizon. They’d fished the stream together that day. She could still smell the scent of ferns and the faint odor of live trout.

It was the last time she’d ever seen her father.

Alex did not have daddy issues. Of course, it’d been hell when her parents died. Terrible that it’d happened in an embassy bombing, but tragedy was an undeniable part of this world. Innocent people were hit by cars, paralyzed skiing. They crashed motorcycles or were victims of natural disasters. One did not forget the unexpected and sudden, but one could overcome any emotional trauma in time. Wounds closed up, scarred over, left a thickened patch of skin to protect any nerves that survived below that surface.

For Alex, her parents were there one day, and gone the next. A solid and full home-life erased and then replaced. Sure, she’d been pissed off at the world for a few years, cursed The Universe and all that. What pre-teen wouldn’t? But she’d been well cared for, well loved, and eventually she came to the conclusion that though a person might yearn for order, she operated ever in chaos. Predict the next year? The next day? Most times you couldn’t even predict the next minute.

And Alex was fine with that. This early understanding had made life easier on her in ways, and it’d certainly contributed to her success on the job. Yet tonight was different. No way in hell would she have ever predicted her father re-appearing from the grave…so much for deadened nerves. Suddenly, Alex was no longer an orphan, she was just left behind. Abandoned.

Alex realized, with a building hollowness in her stomach, that she had been discarded.

She flipped the pages forward to see if she’d drawn any other scenes of the chalk stream in this book, but the rest were places she’d traveled to on nonofficial business. Geneva, Sao Paolo, Costa Rica. She paused on a page that showed the Place du Bourg-de-Four in Geneva’s Old Town, where Jack Pope—the self-described nomadic salesman—sat at the edge of the Mont Blanc Bridge. Also a last meeting.

Wearing dark wash jeans and a charcoal Harrington jacket, he held a baguette in one hand and an espresso in the other, as the alternating Swiss and Geneva flags flapped in the background. She could almost smell the melting snow mixed with the annual tulip festival, and remembered how he’d laughed while telling her—with the betrayal of an English accent—that he wasn’t the sort of man who drank tea.

Jack’s dark blond hair was short in the drawing, making him look younger than his mid-thirties. Alex used to run her hands through that hair as they made love. She swallowed hard and shook the thought away. It was her own doing. She’d kept Jack at arm’s length, refused to let him get too close to her, after all.

Alex turned to a blank page, untied her leather fold of pencils, and closed her eyes for a moment.

Drawing to Alex was much like writing in a journal or deep meditative yoga was for others. They called it eidetic, but all Alex knew was it helped her process information, occupying her conscious mind while releasing the subconscious. Drawing was the primary tool she used to analyze complex situations.

This time she drew to remember.

Alex thought of her father standing in the restaurant entry, unmoving as the light cut across his face and he stared straight at her. She let her hand glide across the page, her pencil creating the long, oval contours of a face, eyes high-set, jaw strong. She outlined the hair and ears next, and finally the nose and lips. First the lines of the face, then the lines on the face. Each of them darkened as the image became more grounded, more certain. The person before her came to life.

Edgar Winter.

Breathing in easy cadence, Alex added line-by-line, long strokes and shorter ones, detail-by-detail, with fluid movements and a soft touch to the page. This was what she needed to calm herself, and she fell into the work, deeper and deeper, until she could finally hear words rising from the man taking shape before her.

“See?” her father asks, and she gazes to where he points, while standing up to her waist in the cool meadow stream.

“No. Where?” Alex bends low, careful to keep her rod’s tip from disturbing the surface.

“Watch for the movement first.” Her father puts a strong arm around her shoulder and bends with her, pointing to the same spot. “There.”

A strip of dark silver flashes below the ripples.

“I see it!” Alex says, and moves to cast.

“Good,” he says, but holds her arm down, preventing her from raising the rod. “Now watch the movement. Follow him with your eyes only. Stay still.”

“He’s right there, though. I see him. I can—”

“No,” he says, without ever taking his eyes off the water. “You need to time it. Find the right moment. Then make your play.”

“When he surfaces again?”

Her father nods. “This is why trout get caught, Alex. They have patterns. Remember that.” And he peers at her for a long second.

Alex looks up and searches her father’s face. It’s an opening, an intentional one, and she knows it. How does she take it? How does she ask?

“You like fishing, Daddy?”

“Fishing is not something I do. It’s something I am.”

Alex smiles at him, but doesn’t have the guts to ask him what she really wants to know.

Her father knows it. He says, “That’s not the question you were thinking of, is it, Alex?” He glances up at Alex’s mom sitting under a tree, reading, then adds in a low voice, “Your mother told me your concerns, so go ahead and ask. You’re old enough to know… and you should, so you can understand why I’m not always here.”

Holding her breath, she waits, unsure she wants to even hear the full truth, but certain she’s tired of the half lies. So she asks, as bravely and brazenly as she can, “Where do you really go?”

She searches his eyes after he tells her. “Does Mom know?”

“Of course. Only in fantasy do the spouses remain ignorant. And how could that really work, me leaving for weeks or even months at a time?”

Alex stands silent, nothing to say to that.

“But she doesn’t know details. No one does. The movies get that part right.”

They stand there for what seems like a good while, the water lapping the rocks at the edge of the stream. Suddenly, without ceremony, her father squeezes Alex’s shoulder and points to the water.

“Now.”

Four

Alex startled awake to the sound of someone rapping the butt of a black pistol on the car window. With no gun of her own, she whirled away and shielded the back of her head with the hard bone of an elbow. Best she could do in the tight space.

“Easy now.” The m

an’s muffled voice sounded distant in the solid Mercedes chamber. “Just need to move your car, is all.”

Squinting, Alex turned and peered through the glass.

The man wore a puffy down jacket and light brown gloves with black marks on them. He was holding up a black cell phone, not a pistol, and pointing to a truck in front of them, then the large wooden double doors behind. Alex was blocking his entrance.

“Right,” she said, holding up a hand and wincing at the soreness of her shoulder.

Alex set aside the sketchbook and started the car, revving the engine to get the heat going. According to the digital read on the dash, the temperature had dropped to nine degrees Celsius outside, and felt like twelve or so in the car, which translated to the low fifties in Fahrenheit. She checked her watch as she pulled around the tall truck. Just after five a.m., no wonder it was still dark.

Alex drove alongside the river, cutting through Piccadilly before hitting Buckingham Palace. With white lights strung over the street in the shape of presents, bows, and huge umbrellas, as well as a row of twenty-foot-high blue Christmas trees, Oxford Street rivaled the winter displays of Saks and Rockefeller Plaza in New York City. At this hour, though, the roads were empty of people scurrying from store to store and lugging oversized sacks of purchases. She switched the phone on again, but there was still nothing from Langley so she kept her objective simple. Get back to the hotel and change out of the dress.

She was staying at the Marriott in Grosvenor Square, partly because it was the same hotel where she and Jack had stayed during their first trip to London last year.

Call her romantic.

Truth was, Alex liked the contemporary Maze bar there, and the Gordon Ramsey menu rarely disappoints. That, and she liked being able to look across the green at the US Embassy.

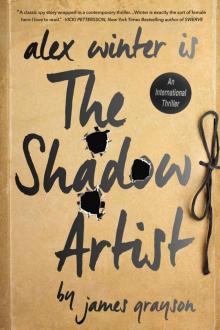

The Shadow Artist

The Shadow Artist